Mining and the Battle of Messines

2018-08-20

“The signal for its beginning was the most terribly beautiful thing, the most diabolical splendour, I have seen in war. Out of the dark ridges of Messines and Wytschaete and that ill-famed Hill 60, for which many of our best have died, there gushed out and up enormous volumes of scarlet flame from the exploding mines and of earth and smoke, all lighted by the flame, spilling over into fountains of fierce colour, so that all the countryside was illuminated by red light. Where some of us stood watching, aghast and spellbound by this burning horror, the ground trembled and surged violently to and fro. Truly the earth quaked.”

Those were the words of journalist Philip Gibbs upon seeing the beginning of the Battle of Messines in the First World War.

First World War and Military Mining

It was the 4th of August 1914. The British Empire declared war on Germany for its aggressions in Belgium. Because it was part of the British Commonwealth of nations, Australia would enter the war. During the first month of the war, it became abundantly clear that this was to be a different kind of war than the Empires previous colonial wars. During the Battle of Liege the Germans were able to smash Belgian fortresses with 420mm shells. On the 22nd of August, 27,000 French soldiers were killed in one day of battle. In order to keep the soldiers alive, they had to dig in first with trenches, then funk holes, then gun emplacements, then mines. These all needed to be dug in varied terrain from the hard rock of the Alps to the mud of Passchendaele. In order to dig in, the Armies needed someone to tell them what the subsurface was like. The Armies needed geologists.

Mining, or Undermining, is a technique used in Warfare were soldiers dig tunnels underneath enemy fortifications to try and destroy them or advance past them. It had a long history, from Marcus Fulvius’s siege of Ambracia, where, according to Polybius, the Romans dug tunnels towards the Aetolian positions, only to be rebuffed by poison gas (Does that not remind you of the later war), all the way to the Modern day, where insurgent forces in Syria have dug tunnels underneath Syrian government positions. In the modern day, these mines have been filled with explosives, allowing large positions and thousands of men to be killed in a moment.

It was the Germans who first started Mining in the Great War. On 20 December of 1914, 340 kilograms of explosives would detonate under Indian positions at Festubert, allowing the German infantry to take that part of the line with relative ease. The British soon got their own tunneling corps after that.

And then, in 1915, the Minister of Defence decided to raise the tunneling corps in Australia. At first, they were to be deployed to Egypt, but Major TWE David had to inform the army that tunnels would be hard to dig in the sand, so, instead, they were sent to the Western Front.

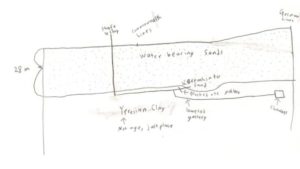

When they Tunneling Corps arrived, they would first have to get the Geology of the front down pat, so they drilled core samples all along the front. Luckily, the large-scale geology was simple. It could be divided it into two broad sections. The blue clay and fine sands of Flanders to the North and the Chalk to the South towards Picardy. He then used drill cores to further subdivide the geology of the Flanders region into the Clay Country, the Sand Country, and the Sandy Clay Country.

In the Flanders region, it was determined that the best place to put dugouts and dig tunnels was in the clay layers, between the porous water-bearing sand layers.

The Chalky areas in the South provided different problems, where the level of groundwater would vary between Spring and Autumn, forcing Miners to abandon their tunnels.

There was also the issues where these two worlds collided at Vimy Ridge. There was an important enemy strong point called “The Pimple.” The Pimple was above sand and clay, but the corresponding Entente lines were on Chalk. The Commonwealth forces were going to use this to their advantage (As it was possible to mine silently in clay). But before this could come to fruition, the Canadians stormed Vimy and took the Pimple with only a few of the mines completed.

Messines

But, the king of the Mining operations in the Great War would be at Messines, Belgium. The Commonwealth forces had spent countless lives attempting to take Hill 60. The position could enfilade the Entente positions from the safety of Concrete Pillboxes. The previous assaults had had mines associated with them, but they only were on the Hill itself, so the Commonwealth forces were only able to take the Hill itself, creating a salient, that was too costly to hold. So for this assault, not only would they need to take Hill 60, but the surrounding area and the Mining operations would have to take place across a large scale across the front.

Since Messines is further North than Vimy, it was firmly in Sandy Clay country, and there were issues both geological and martial that faced the miners. The Germans had geophones from which they would listen for the sounds of the pickaxes. They would then mine towards the Entente tunnels, and detonate explosives above or below the tunnels, killing the miners inside. If they misjudged, the tunnels might break into each other, leading to fierce fighting underground. To counter the countermining, Entente forces would dig complicated false trenches in a ‘noisier’ fashion than the active mines, encouraging the Germans to attack those tunnels, leaving the real ones undisturbed.

The miners also had to deal with the dirt they were removing from the tunnels. Normally, in a mine, one can just pile the gangue wherever they want, but in this case, the Germans would be watching. The blue clay that the tunnelers would be driving their galleries through didn’t occur on the surface, so any sight of it would confirm that a mine was being dug, and possibly the locations of the shafts, which would provide excellent targets for artillery.

One of the main problems for the tunnelers would lie in this blue clay. It was not just a uniform layer underneath the surface. Long before humans had been mining, the sand in the area had been deposited. The clay was then unevenly deposited on top, and, further confusing matters, rivers cut through the clay layer, filling in with sand. This made the prized clay layer of varying thickness, which is a major problem if you need to avoid water (And pumping the water out was a problem because the Germans potentially could hear the pumps operating). If the tunnels breached out of clay layers into the sand, they’d either be flooded by water following gravity from above, or from the artesian water below. So first, at Boyle’s Farm, the tunnelers had to drive a steel tube 28 meters through the alluvial sands into the clay, then drive their gallery until they hit sand and sealed off the tunnel.

Now normally, to find the extent of this clay layer, geologists could just drill a few boreholes over the mine and develop an accurate map of the subsurface, but it’s hard to set up a drilling rig in the middle of No-Mans Land. Seismology, in addition to being a very new field (The first patents being filed in 1914), also would have issues, as its hard to get a good sound recording if you have constant Artillery noise interfering with your data. The geologists had to look at old Belgian core samples and analyze other successful galleries to determine how they should change the gallery to successfully tunnel underneath the German trenches.

And finally, on the 7th of June 1917, everything came together. 21 mines had been emplaced underneath the German Lines. The night before, General Plumer is reported as saying “Gentlemen, I don’t know whether we are going to make history tomorrow, but at any rate we shall change geography”

The soldiers moved to their jumping off points in the middle of No Mans Land, Squadrons of aircraft flew overhead to disguise the sound of the approaching tanks. Then, the artillery stopped. Birds could be heard singing overhead. It was almost peaceful.

Nineteen of the mines went off at 3.10 AM in what would be the largest intentional explosion until nuclear weapons were developed (Though the Halifax explosion would dwarf it a few months later). Ten thousand soldiers had been killed in an instant as the German Army had reinforced their front line in anticipation of the attack

Father William Doyle, a Jesuit Priest attached to the British Army recorded the incident as thus: Even now I can scarcely think of the scene which followed without trembling with horror. Punctually to the second at 3.10 a.m. there was a deep muffled roar; the ground in front of where I stood rose up, as if some giant had wakened from his sleep and was bursting his way through the earth’s crust, and then I saw seven huge columns of smoke and flames shoot hundreds of feet into the air, while masses of clay and stones, tons in weight, were hurled about like pebbles. I never before realized what an earthquake was like, for not only did the ground quiver and shake, but actually rocked backwards and forwards, so that I kept on my feet with difficulty.

As an aside, Geologists out there will instantly be able to recognize the Rayleigh and Love waves that are described in that quotation.

Back to the history: After the blasts, the British artillery started firing gas shells at the German gun positions, and a Creeping barrage started in front of the Commonwealth troops, moving at a rate of a hundred yards every two minutes. The troops advanced past stunned German soldiers. Private Gladden of the 11th Northumberland Fusiliers described the advance “The crater, which I expected to see as an immense jagged hole in the ground, was actually a large flat bottomed depression like a frying pan, clear and clean from debris except at the further edge, where vestiges of one of the enemy’s trenches showed through its side. The poor devils caught in that terrible cataclysm had no chance. Yet what chance was there for anyone in that war of guns and mathematics?… …Here and there black fountains of earth were thrown up as heavy enemy shells burst in the wilderness and put a finishing touch to that scene of desolation. I could survey the whole of the famous hill and, away in front, the tree stumps of Battle Wood; and it occurred to me that until that day no man had, during those many months since the first battles, stood on that same ground in daylight and lived”

The attacks were a success, and these combined arms operations would become the norm. This battle was a microcosm of everything that was developed in the war. From the air and armor support to the advances of artillery that allowed for creeping barrages.

But, this would also be the swansong for First World War military mining. Afterward, the war became too mobile for mining with things like the German Spring Offensive (The opening of which is the setting of my favorite straight play “Journey’s End”)

There was a final note in the Battle of Messines. One of the unexploded mines from the battle was struck by lightning in 1955, killing a cow. The math nerds among you might notice that Twenty One mines minus Twenty explosions, leaves One. This means there is still a large number of explosives hiding underneath this Belgian town, but, such is life in that part of the world. There is something called the Iron Harvest, where every year, farmers retrieve unexploded ordnance from their fields. I once watched a video, where a farmer hitting something on his tractor knew instantly that it was an artillery shell, not a rock, based on how his tractor reacted. There are areas in France known as the Zone Rouge, where people were never allowed to resettle because of the huge quantities of unexploded ordnance in the area. While WWII was much more destructive on a whole, the First World War on the Western Front had years of fighting over thin strips of land

Finally, notes on the people I’ve mentioned. TWE David would be knighted for his service in the war. Plumer would be made a Viscount. Private Edgar Norman Gladden would publish his accounts of the war in 1974. Philip Gibbs would serve in the Ministry of Information in the Second World War. Father William Doyle would be killed two months later at Langemarck.

If you want to see what the explosion was like, here is a video of the Hawthorne Ridge Redoubt explosion from the opening of the Somme

As a postscript, I’d like to close with a quotation from William March’s Company K, a serial inspired by his service during the war.

“You can always tell an old battlefield where many men have lost their lives. The next spring the grass comes up greener and more luxuriant than on the surrounding countryside; the poppies are redder, the corn-flowers more blue. They grow over the field and down the sides of the shell holes and lean, almost touching, across the abandoned trenches in a mass of color that ripples all day in the direction that the wind blows. They take the pits and scars out of the torn land and make it a sweet, sloping surface again. Take a wood, now, or a ravine: In a year’s time you could never guess the things which had taken place there.

I repeated these thoughts to my wife, but she said it was not difficult to understand about battlefields: The blood of the men killed on the field, and the bodies buried there, fertilize the ground and stimulate the growth of vegetation. That was all quite natural she said.

But I could not agree with this, too-simple, explanation: To me it has always seemed that God is so sicked with men, and their unending cruelty to each other, that he covers the places where they have been as quickly as possible.”

Incomplete sources

Branagan, D., 2005, T.W. Edgeworth David: A Life: Geologist, adventurer, soldier and ‘Knight in the old brown hat’: Canberra, National Library of Australia, 648p.

Brooks, A.H., 1920, The Use of Geology on the Western Front: USGS Professional Paper 128, p. 85-124.

David, M.E., 1937, Professor David The Life of Sir Edgeworth David: London, Edward Arnold & Co., 320 p.

Gibbs, P., 1918, From Bapaume to Passchendaele, on the Western Front, 1917: New York, New York, George H. Doran Company, 462 p.

King, W.B.R., 1919, Geological Work on the Western Front: The Geographical Journal, v.54, 4, p. 201-215.

Offer, J., 2013, Commonwealth First World War dead visualised: http://www.codehesive.com/commonwealthww1/ (accessed November 2016).

Small, S., Westwell, I., Westwood, J., 2002, History of World War I: Tarrytown, Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 960p.

Recent Comments